“Security Analysis of SMS as a Second Factor of Authentication”

Communications of the ACM, December 2020, Vol. 63 No. 12, Pages 46-52

Practice

By Roger Piqueras Jover

“In the age of large-scale cyberattacks, one of the largest civilian communication systems must rely on privacy protocols far more sophisticated than just basic implicit trust anchored in the base station looking like a legitimate station.”

The internet started becoming the main reason that household PSTN (public switched telephone network) lines stayed busy sometime in the mid to late 1990s. Over the next decade, a number of online services completely changed the interaction of society with technology. From email to the dawn of e-commerce, these services increasingly tied people to technology and the Internet.

Although the concept of a password was prevalent in many technology disciplines and domains, the general public had little knowledge of it, with the exception of PINs for their debit cards. It was the Internet that introduced the concept of password security to them. From that point on, people realized they had to remember passwords to access their email accounts, favorite e-commerce sites, and so on.

At that time, a password was all it took to unlock an account, and password requirements were very loose. The cybersecurity landscape was nowhere near as challenging as it is now, particularly when it comes to the security of consumer accounts. There were exceptions for certain industries, such as banking, where password requirements were slightly more stringent and a hidden form of two-factor authentication, based mainly on IP geolocation, was used before it became an option for other sites. Nevertheless, the average consumer generally needed just a simple password to access even highly critical repositories of data, and the same password was often reused for multiple accounts.

Today Internet security requires much more attention. A good example of what can go wrong is the hacking ordeal detailed by a technology reporter for Wired who was not using two-factor authentication for his email account. [link below] Email accounts have become, over the years, not only large repositories of highly sensitive and private data, but also single points of failure for digital footprints on the Internet. For example, the majority of online services allow for the resetting of a password by sending an email to the user’s main email account. As a result, if an email account gets compromised, many other accounts can also be compromised in short order.

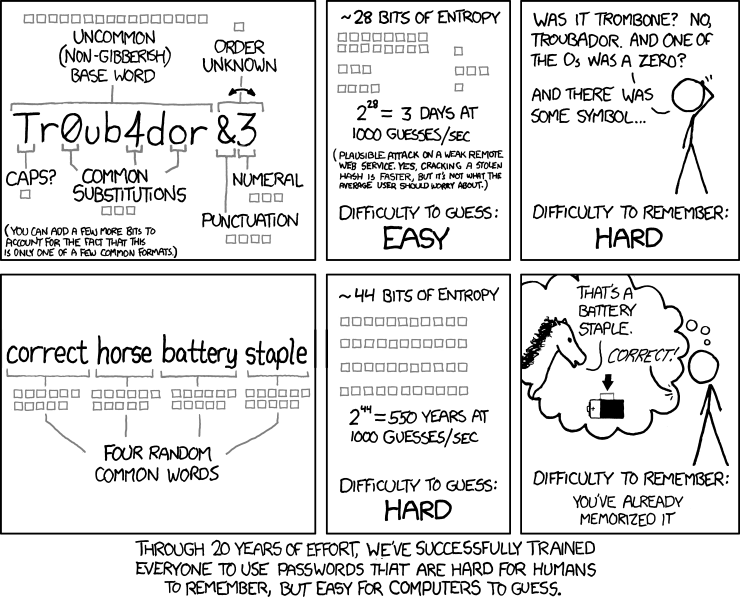

As the security-threat landscape has changed, so too have the way passwords are used and their complexity requirements. Although many online services did not really adhere to best practices, it became widely acknowledged that passwords should be highly complex in order to maximize their entropy and, thus, substantially increase the amount of time it would take to crack them.

Eventually, though, some scientific studies and a viral online cartoon argued that increasing password complexity was not the right solution. Pass-phrases are proven to have much higher entropy and are much easier to remember. On the other hand, forcing password rotation, in combination with a strict password complexity policy, has been shown to result in much weaker passwords. Moreover, as a rule of thumb, it is now acknowledged that a password might not necessarily have to be rotated if it is not present in any of the public repositories of leaked credentials in the wild.

Along with the ongoing challenge of making passwords secure but still usable and easy to remember, the security industry recognized the security of an online account should not be protected only by something you know (your password). Somewhat similar to the banking approach, which requires something the user has (for example, a debit card) and something the user knows (for example, the card’s PIN), online accounts started to support, and in some cases mandate, the use of two-factor authentication. The second factor needed to be something the user has—the obvious and simple choice was clear from the beginning: the user’s smartphone.

Enabling two-factor authentication for online accounts is critical to their security. Everyone should enable this feature in (at the very least) their email accounts, as well as other accounts that store critical and sensitive data such as credit card numbers. Crypto-currency exchange accounts, which are commonly the target of cybercriminals, should also be secured by multiple forms of authentication. The potentially high monetary value of what these accounts protect makes them an interesting case study of what might be the best choice for a second form of authentication. For example, while SMS (short message service) as a second form of authentication is a good idea for certain types of online accounts, it is not the best option for those who own a large amount of cryptocurrency in an online exchange.

SMS-based authentication tokens are popular options for securing online accounts, and they are certainly more secure than using a password alone. The history of cellular network security, however, indicates that SMS is not a secure method of communication. From rogue base stations and stingrays to more sophisticated attacks, there are a number of known methods to eavesdrop on and brute-force text messages, both locally and remotely. As such, this method is not the most reliable for accounts that store assets with a high financial value, such as cryptocurrencies.

This article provides some insight into the security challenges of SMS-based multifactor authentication: mainly cellular security deficiencies, exploits in the SS7 (Signaling System No. 7) protocol, and the dangerously simple yet highly efficient fraud method known as SIM (subscriber identity module) swapping. Based on these insights, readers can gauge whether SMS tokens should be used for their online accounts. This article is not an actual analysis of multifactor authentication methods and what can be considered a second (or third, fourth, and so on) factor of authentication; for such a discussion, the author recommends reading security expert Troy Hunt’s report on the topic. [link below]

(Full disclosure: the author uses SMS to secure some rather vanilla online accounts, mainly those that do not require storing a credit card number or other sensitive financial information.)

About the Author:

Roger Piqueras Jover is a senior security architect with the CTO Security Architecture Team at Bloomberg, where he is a technical leader in mobile security architecture and strategy, corporate network security architecture, wireless security analysis and design, and data science applied to network anomaly detection. He is a technology adviser on the security of LTE/5G mobile networks and wireless short-range networks for academia, industry, and government.

Related Articles:

VoIP: What is it good for?

Sudhir R. Ahuja and J. Robert Ensor

https://queue.acm.org/detail.cfm?id=1028897

Communications Surveillance: Privacy and Security at Risk

Whitfield Diffie and Susan Landau

https://queue.acm.org/detail.cfm?id=1613130

ACM CTO Roundtable on Mobile Devices in the Enterprise

Andrew Toy, André Charland, George Neville-Neil, Carol Realini, Steve Bourne, Mache Creeger

https://queue.acm.org/detail.cfm?id=2016038

How Apple and Amazon Security Flaws Led to My Epic Hacking

Mat Honan

https://www.wired.com/2012/08/apple-amazon-mat-honan-hacking/

Beyond Passwords: 2FA, U2F and Google Advanced Protection

Troy Hunt

https://www.troyhunt.com/beyond-passwords-2fa-u2f-and-google-advanced-protection/

Password Strength