“Where computing might go next”

MIT Technology Review, October 27, 2021

Computing

by Margaret O’Mara

“The future of computing depends in part on how we reckon with its past.”

If the future of computing is anything like its past, then its trajectory will depend on things that have little to do with computing itself.

Technology does not appear from nowhere. It is rooted in time, place, and opportunity. No lab is an island; machines’ capabilities and constraints are determined not only by the laws of physics and chemistry but by who supports those technologies, who builds them, and where they grow.

Popular characterizations of computing have long emphasized the quirkiness and brilliance of those in the field, portraying a rule-breaking realm operating off on its own. Silicon Valley’s champions and boosters have perpetuated the mythos of an innovative land of garage startups and capitalist cowboys. The reality is different. Computing’s history is modern history—and especially American history—in miniature.

The United States’ extraordinary push to develop nuclear and other weapons during World War II unleashed a torrent of public spending on science and technology. The efforts thus funded trained a generation of technologists and fostered multiple computing projects, including ENIAC—the first all-digital computer, completed in 1946. Many of those funding streams eventually became permanent, financing basic and applied research at a scale unimaginable before the war.

The strategic priorities of the Cold War drove rapid development of transistorized technologies on both sides of the Iron Curtain. In a grim race for nuclear supremacy amid an optimistic age of scientific aspiration, government became computing’s biggest research sponsor and largest single customer. Colleges and universities churned out engineers and scientists. Electronic data processing defined the American age of the Organization Man, a nation built and sorted on punch cards.

The space race, especially after the Soviets beat the US into space with the launch of the Sputnik orbiter in late 1957, jump-started a silicon semiconductor industry in a sleepy agricultural region of Northern California, eventually shifting tech’s center of entrepreneurial gravity from East to West. Lanky engineers in white shirts and narrow ties turned giant machines into miniature electronic ones, sending Americans to the moon. (Of course, there were also women playing key, though often unrecognized, roles.)

In 1965, semiconductor pioneer Gordon Moore, who with colleagues had broken ranks with his boss William Shockley of Shockley Semiconductor to launch a new company, predicted that the number of transistors on an integrated circuit would double every year while costs would stay about the same. Moore’s Law was proved right. As computing power became greater and cheaper, digital innards replaced mechanical ones in nearly everything from cars to coffeemakers.

A new generation of computing innovators arrived in the Valley, beneficiaries of America’s great postwar prosperity but now protesting its wars and chafing against its culture. Their hair grew long; their shirts stayed untucked. Mainframes were seen as tools of the Establishment, and achievement on earth overshadowed shooting for the stars. Small was beautiful. Smiling young men crouched before home-brewed desktop terminals and built motherboards in garages. A beatific newly minted millionaire named Steve Jobs explained how a personal computer was like a bicycle for the mind. Despite their counterculture vibe, they were also ruthlessly competitive businesspeople. Government investment ebbed and private wealth grew.

The ARPANET became the commercial internet. What had been a walled garden accessible only to government-funded researchers became an extraordinary new platform for communication and business, as the screech of dial-up modems connected millions of home computers to the World Wide Web. Making this strange and exciting world accessible were very young companies with odd names: Netscape, eBay, Amazon.com, Yahoo.

By the turn of the millennium, a president had declared that the era of big government was over and the future lay in the internet’s vast expanse. Wall Street clamored for tech stocks, then didn’t; fortunes were made and lost in months. After the bust, new giants emerged. Computers became smaller: a smartphone in your pocket, a voice assistant in your kitchen. They grew larger, into the vast data banks and sprawling server farms of the cloud.

Fed with oceans of data, largely unfettered by regulation, computing got smarter. Autonomous vehicles trawled city streets, humanoid robots leaped across laboratories, algorithms tailored social media feeds and matched gig workers to customers. Fueled by the explosion of data and computation power, artificial intelligence became the new new thing. Silicon Valley was no longer a place in California but shorthand for a global industry, although tech wealth and power were consolidated ever more tightly in five US-based companies with a combined market capitalization greater than the GDP of Japan.

It was a trajectory of progress and wealth creation that some believed inevitable and enviable. Then, starting two years ago, resurgent nationalism and an economy-upending pandemic scrambled supply chains, curtailed the movement of people and capital, and reshuffled the global order. Smartphones recorded death on the streets and insurrection at the US Capitol. AI-enabled drones surveyed the enemy from above and waged war on those below. Tech moguls sat grimly before congressional committees, their talking points ringing hollow to freshly skeptical lawmakers.

Our relationship with computing had suddenly changed.

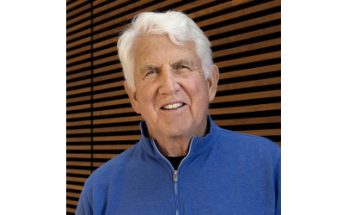

About the Author:

Margaret O’Mara is a historian at the University of Washington and author of The Code: Silicon Valley and the Remaking of America.