“Information: ‘I’ vs. ‘We’ vs. ‘They’”

Communications of the ACM, May 2022, Vol. 65 No. 5, Pages 45-47

Viewpoint

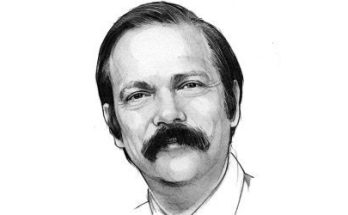

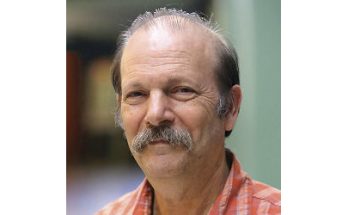

By Reinhard von Hanxleden

“Assessments concerning privacy can hardly be completely neutral and may underlie some cultural bias.”

In his May 2021 Vienna Gödel Lecture, Moshe Vardi made the case for a moral “trilemma.” Paraphrasing Vardi, it referred to the increasing power of online content, including the power to seriously endanger the very foundations of a society, and the question of who should control that power. Should it be: private industry, as providers of the platforms; the government, representing the public; or nobody at all, following a constitutional imperative of free speech? We are just beginning to find answers to these questions, and different societies are taking different approaches.

Here, I present another “trilemma,” which is related in that it is also about information sovereignty, but different in that it concerns what we usually call “personal data.” To consider a current example, a bit representing whether a person is COVID-infected or not is certainly of a rather personal nature. But that does not answer yet whose data it is—and who should decide about whose data it is. Is it my data, not to be shared with anybody unless I explicitly give my consent? Or is it our data, because as a society we need this information, at least in some anonymized/aggregated form that is still precise enough to be truly useful, to treat a pandemic effectively? And do they, who effectively decide this, decide that question as I or we would do—if we were asked?

‘I’ vs. ‘We’—The Cultural Context

The answers to the preceding questions may depend on the cultural context. According to a recent panel on how Asian countries have handled the pandemic, there have been effective laws for protecting personal data in Taiwan for a long time, especially in the medical field, but apparently there is a societal agreement that data is systematically aggregated and evaluated.1 In contrast to these countries, it was difficult in Germany to, for example, introduce compulsory COVID tests in schools.

Along similar lines, consider the discussion around the introduction of a national COVID warn app. One horror scenario initially circulated was that the cellphone would sound an alarm as soon as one met an infected person. A horror scenario not because it would indicate imminent personal danger for a contact person, but because the infected would then be robbed of their anonymity. Of course, the Corona app was designed differently from the start, namely in such a way that if someone tests positive, others that were in contact with that person in the past are informed. One should not even meet infected people, because they should quarantine anyway.

‘They’

Quoting from a (translated) article from May 25, 2021, in the online education magazine News4Teachers: “The data protection officer of Baden-Württemberg warns against using Microsoft products in schools—for fundamental reasons. If the state government follows his line, all software from U.S. corporations would have to be banned from German educational institutions. However, there is now resistance to such IT fundamentalism: school administrators see the work of their colleges as being threatened. A petition on the Net calls for more pragmatism in data protection.”

A subsequent survey conducted on that case revealed that among the 5,000+ participants, approximately 75% were in favor of keeping the MS products, and even 82% among the 3,000+ teachers. It remains to be seen whether “our” fairly clear public will can trump “their,” the data protection officials’ objections.

About the Author:

Reinhard von Hanxleden is a professor of computer science at Kiel University in Kiel, Germany.